The College faces unique challenges related to pre-major advising

Pre-major advisors are not always knowledgeable about major requirements

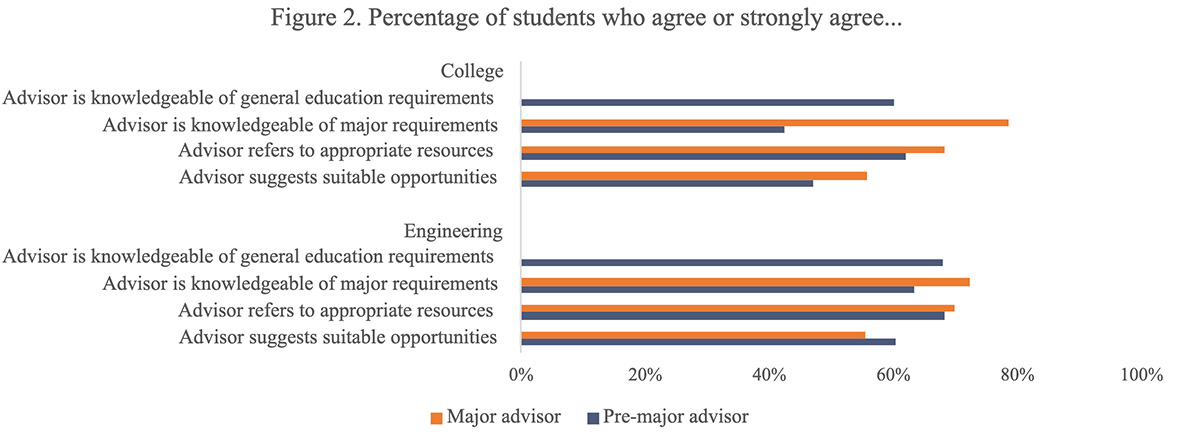

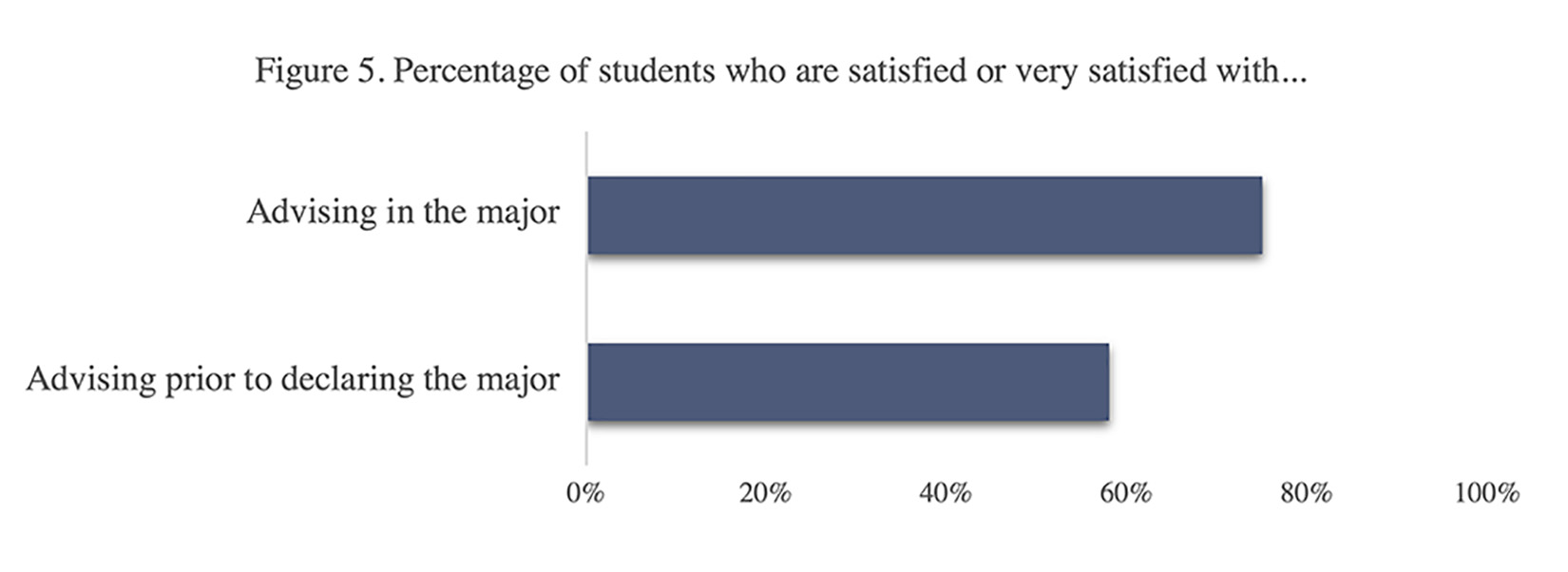

The College faces unique challenges along two dimensions related to pre-major advising. The first pertains to a lack of knowledge among pre-major advisors about major requirements outside of their field. A comparison of major and pre-major advisors in the College indicates that the advisors are rated similarly on many dimensions, with the biggest difference observed regarding advisor knowledge of pre-major requirements (as seen in Figure 2, comparing orange and blue bars for the College). In the Spring 2021 Advising Survey, 79% of students in the College agree/strongly agree that the major advisor is knowledgeable about their major requirements while 43% of students agree/strongly agree that their pre-major advisor is knowledgeable about their major requirements.10

Students’ dissatisfaction with pre-major advising in the College is also prominent in students’ qualitative comments in the Spring 2021 Advising Survey and listening sessions. Comments such as: “my pre-major advisor was nice but did not know anything about my major requirements” or “my pre-major advisor was not helpful at all as she did not know anything about my area of interest” came up repeatedly. Indeed, interest mismatch was the most common negative comment about advisors recorded in open-ended responses among College students in the Spring 2021 Advising Survey.

While students in the College typically do not declare a major until the spring of the second year, a number of majors (particularly in the STEM fields, including some social sciences) have extensive requirements and course sequences that require careful planning. Students interested in those majors thus have to begin taking specific major-related coursework in the first year, and at times may have to take a specific class in a particular semester. Similarly, students who intend to apply for internal transfer to another school often need to complete a range of courses in the first two years to be eligible for transfer.

A lack of opportunities for structured exploration

Due to its size and versatility, the College advises students across a wide spectrum of interests, from those who are undecided or do not have a firm sense of what major or career they may wish to pursue, to those who come determined to major in a particular area and/or pursue a particular career path. In the listening sessions, faculty and staff in the College placed a substantial emphasis on exploration – emphasizing spending the first two years exploring one’s interests. However, there are no structures in place (e.g., no formal connections with the Exploration Team at the Career Center or other formal/structured exploration opportunities) that would facilitate productive exploration of academic and career goals. What exploration often looks like is an advisor asking: “are you sure you want to do x? did you consider y?”, without offering much specific guidance or direction. Moreover, while many topics cross departments and schools, and while many students take classes across multiple schools (and even major and minor across schools), pre-major advisors are not equipped to provide advice about those offerings since they are knowledgeable primarily about offerings in their own departments.

Note on Transfer Students: In listening sessions both faculty and staff noted that transfer students require specialized knowledge and resources that faculty may not have. Those students face challenges similar to first-year students in terms of navigating the University. In the Spring 2021 Advising Survey, transfer students in the College were more likely to meet with their faculty advisors as well as with Association Deans than first-time first-year students, indicating a higher degree of reliance on institutional supports. The survey revealed no notable differences between first-time first-year and transfer students in their satisfaction with advising or knowledge about resources. It is important to closely monitor transfer students’ experiences and ensure that they can take advantage of all UVA has to offer.

Effective and Efficient Communication with Students

As a large, comprehensive university, UVA offers a range of resources

In addition to their primary academic advisor, students at the University have access to a range of resources both within schools and across the University. Dean’s offices in each school include personnel who advise and provide a range of supports and services to students. In addition to the University Career Center, a number of schools have school-embedded career centers. The Office of the Deans of Students serves all students, supporting their personal growth and development as well as assisting with myriad challenges students face on their journeys through college. Moreover, numerous offices support students in their pursuit of an exceptional undergraduate experience, from research opportunities to study abroad, and offices such as OAAA and Multicultural Student Services support underserved populations. Georges Student Center provides a hub for advising activities and many offices meet with students in that space.

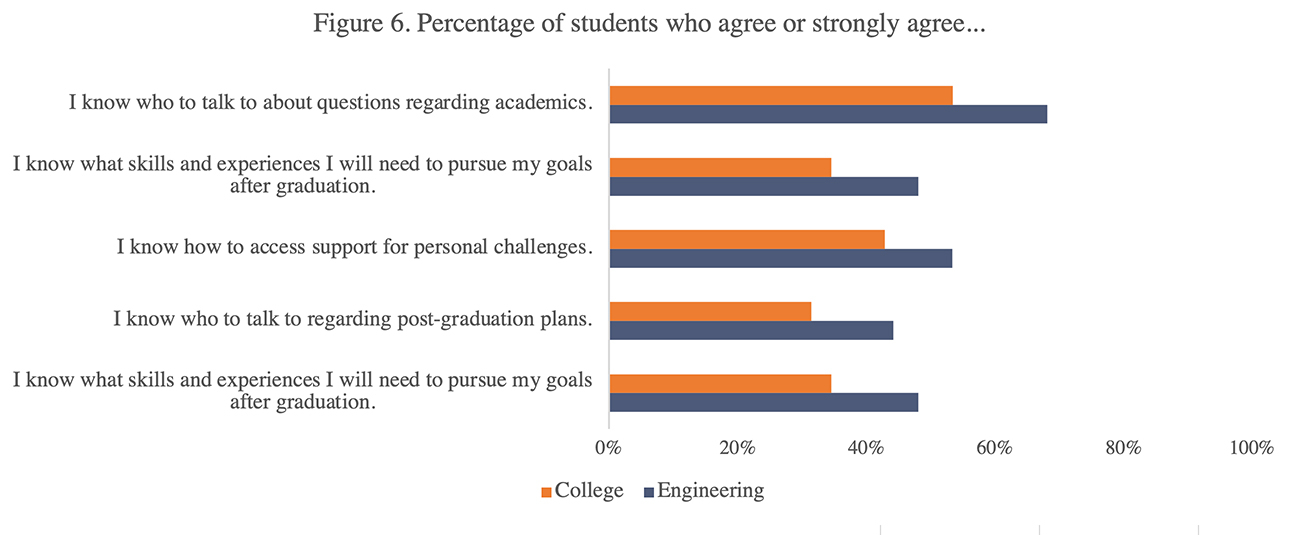

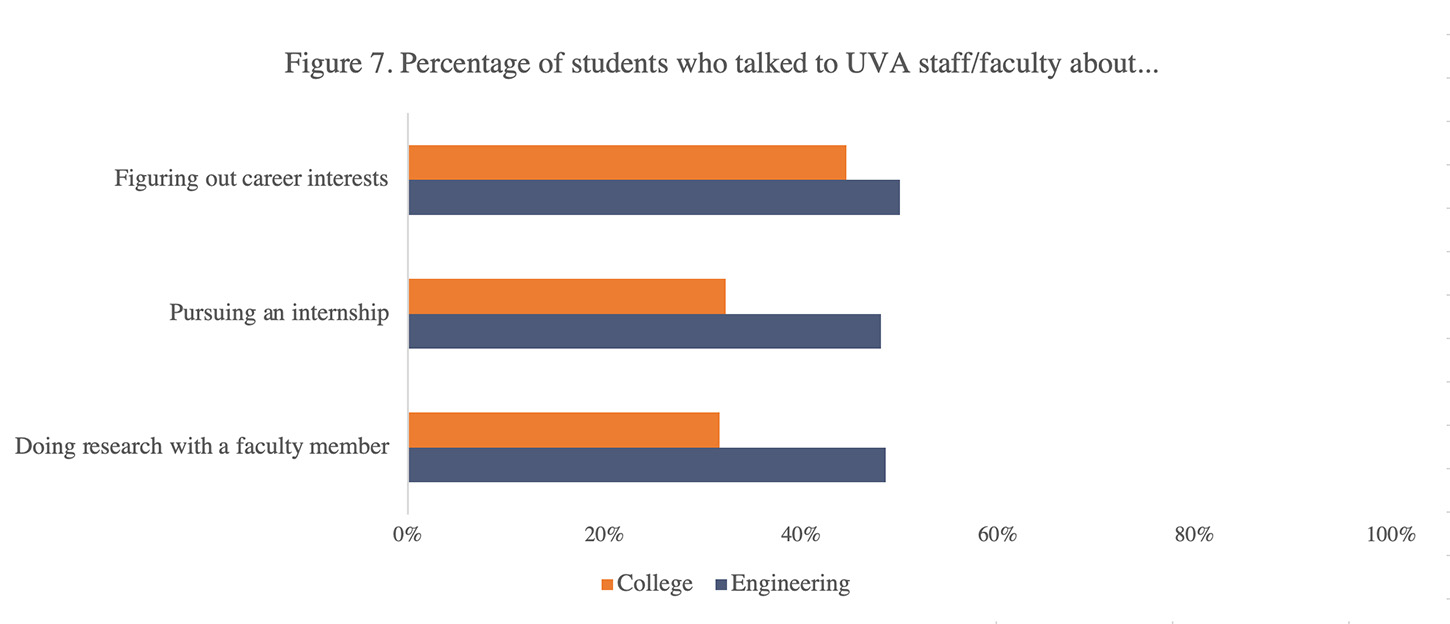

Students do not know who to talk to and how to access resources

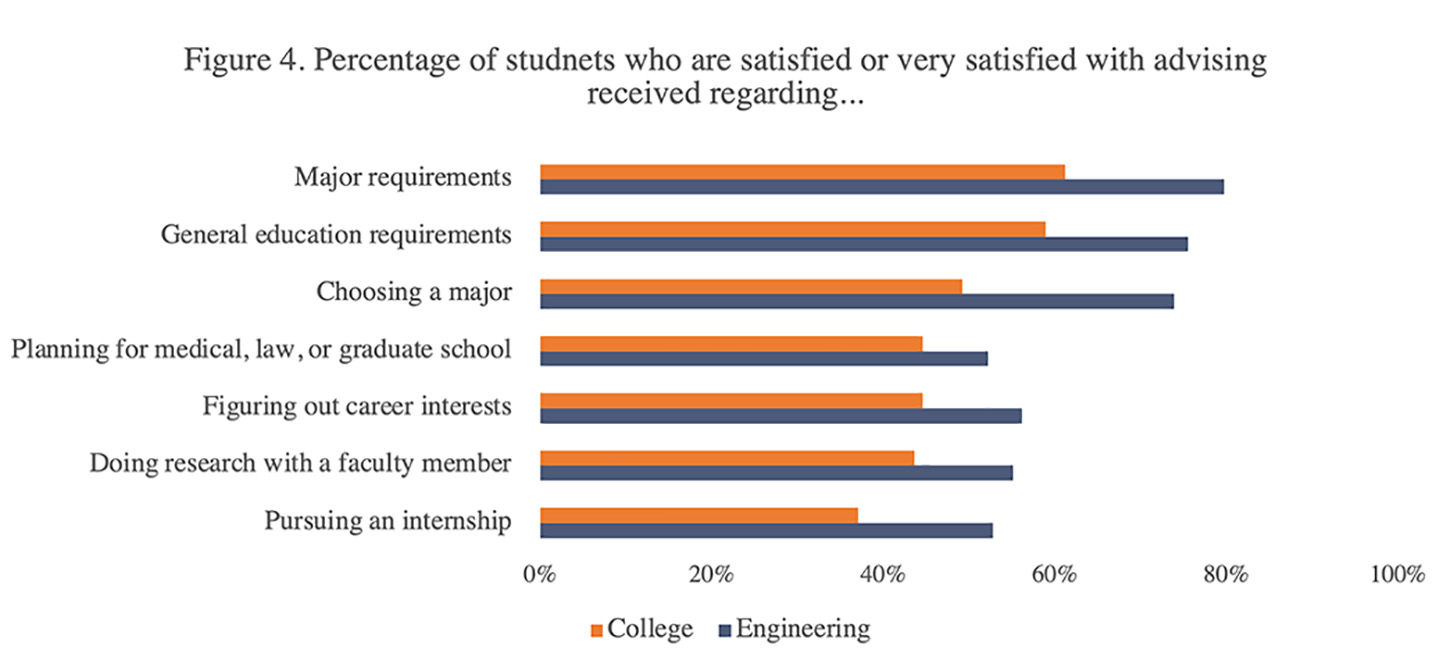

While the University offers a range of resources, students do not know who to talk to about crucial aspects of their experience. For example, only one third of students in the College and under half of students in Engineering agree or strongly agree that they know who to talk to regarding their post-graduation plans or what skills or experiences they will need to pursue their goals after graduation.

Provost

Provost